Articles & Analyses

Dr. Gentiana Sula

Chair of the Authority for Information on the Former State Security Documents

Spaç in the light, access to primary sources for a fair and inclusive memory

The return to the past of communist Albania also brings the remembrance of a deep darkness. The forced labor camp in Spaç, an open wound in our history, was a place where freedom and rights were violated and about 2,000 men, as well as their families, were treated in an inhuman manner. Today, the effort to understand this harsh past is essential so that it never happens again.

By enabling access to primary sources that allow critical thinking and deeper analysis of this dark episode, the documentation of the Spaç archives and the individuals who suffered there was carried out, and testimonies, photos, and letters were collected, bringing an irreplaceable contribution from AIDSSH.

The publication titled “50 Years since the Revolt in the Spaç Prison – Testimonies of the Survivors and Their Families” carries the importance of understanding the history of the Spaç prison and forced labor camp as an emblematic place where the brutality of the communist dictatorship is revealed. Within this camp we find the regime’s victims, their profiles in the society of that time, their plunge into the country’s harshest prison, the sufferings, hardships, and terrible consequences that befell them in the Albanian gulag.

In the darkness of the prison we also find notes of resistance against the regime, something quite rare at that time and in that context. For this reason, this publication also examines the revolt of the Spaç prisoners dated May 21–23, 1973. This revolt, due to its scale, is considered the most important in the prisons of communist Albania. After the violent suppression of the revolt, four political prisoners were executed by firing squad, while about seventy others were re-sentenced. The bodies of those executed remain missing to this day.

Although the typology of this prison camp has been addressed, many facts remain unclear. This study comes to light in the publication to answer many questions, such as: Do we fully understand forced labor as a means of punishment for political prisoners? What were the most pronounced dehumanizing features of the system? At which moments are human rights violations against the prisoners documented?

Through this publication and others of this nature, the Authority aims to fulfill the objectives of

the 2023–2028 Strategic Plan, which defines the presentation of the Authority as a platform for public engagement and understanding of Albania’s communist past. The collected facts support the process of identifying and locating the remains of victims who disappeared or were executed during communism.

The historical and social context of the events covered in the publication

Camp No. 2 was stationed in Spaç in 1968, after more than 17 years as a mobile labor camp where mainly political prisoners were engaged, officially called “Re-education Unit 303, Spaç-Mirditë.” Only in July 1991, with the fall of the communist regime, was the Spaç prison camp permanently closed.

The 1960s represent, in the history of the dictatorship in Albania, the years of great isolation, which in the external context began after Albania’s break with the Soviet Union and the collapse of relations with all the communist countries of the East.

But this period also coincides with the start of a new friendship of the Tirana regime and its alignment with the Chinese model of totalitarianism, another Stalinist version of the dictatorship’s approach to freedom and those who expressed it.

In this period, due to rapid economic decline and lack of resources, the regime increased repression, while this time was also marked by a collapse of trust within the communist leadership itself. As a result, new hostile groups were uncovered.

Human rights violations reached their peak during this phase. In 1961 Albania recorded 4,345 prisoners, divided among six labor camps and four prisons. During the 1960s the class struggle returned even more to Stalinist methods. Trials resumed and death sentences were issued. In these years 139 executions were carried out.

Forced labor was widely used as a repressive and exploitative mechanism for political prisoners throughout the 45-year history of the regime. According to a 1955 U.S. State Department report to the United Nations, forced labor had been massively employed in Albania since the communist regime came to power in November 1944. On May 25, 1951, the Minister of Interior ordered the creation of Camp No. 2, later called “Unit 303.” From 1951 to 1968, political prisoners of this camp worked under compulsion and harsh conditions on the construction of the Peqin–Kavajë, Vjosë–Levan–Fier, and Devoll–Thanë canals. They built the airfield at Ura Vajgurore, Rinas Airport, the Sanatorium, the Meat Combine, the Tannery, the “Gjergj Dimitrov” farm, the Tractor Factory, the Caustic Soda Plant, and the Cement Factory in Elbasan. In 1968 the political prisoners were transferred to the copper and pyrite mine in Spaç. Copper ore was sought after in foreign markets and its price was highly profitable for the closed Albanian economy. The regime began efforts to build a closed processing cycle for the ore, and with Chinese assistance a unit for gold separation from the ore was established. The extraction plan for copper and pyrite was set by the camp command, and the daily quota was announced each day during roll call. Fulfilling the quota and achieving the plan was a non-negotiable requirement. The daily quota for a wagon handler was four wagons: one wagon of pyrite weighed 2 tons and one of copper 1.5 tons. Failure to meet the quota led to punishment and confinement in isolation cells. Data from the “Albakër” archive show that in 1969 the mining system produced only 50 thousand tons of copper, while by 1981 production had risen to about 200 thousand tons per year. Cross-checking archival documents, the Authority’s working group concluded that over 23 years Spaç became a forced labor camp where 2,000 political prisoners produced 2.82 million tons of copper and 1.3 million tons of pyrite, from which 2,500 kg of gold were extracted. Each prisoner who met the quota was paid 10 % of a free miner’s wage. In 1953 it was decided that a prisoner who exceeded the quota by 100 % earned a sentence reduction of 0.02 days per month and payment of 35 % of the work value. If the quota was not met, pay was reduced proportionally. In July 1968 the payment and sentence-reduction reward was removed for political prisoners who exceeded the plan by 25 %, on the grounds that forced labor was serving personal gain rather than re-education. The Spaç camp was located in the northeastern part of Mirdita, in a barren rocky area without vegetation, far from population centers. The harsh terrain is crossed by a stream with water tinted by copper ore. The climate—unbearable heat in summer and severe cold in winter—made Spaç an ideal site for isolating prisoners. Construction began with a few old buildings and later expanded to two main blocks, while nearby copper mine galleries were opened. A few kilometers away the Reps copper enrichment plant was built, and about 10 km to the south stood the Rubik Copper Smelter with its gold-separation plant. In January 1969 the Directorate of Internal Affairs of Mirdita (State Security branch) opened the “Special-Importance Object for Re-education Unit 303, Spaç-Mirditë” file, defining its special status for strict control aimed at “physical security of prisoners, re-education, and work activation.” By early 1980 the number of prisoners ranged from 900 to 1,200. Reports of that year described its significance as “political, economic, and strategic.” Living and working conditions were brutal. Testimonies and documents in this publication describe torture, violence, punishment in isolation cells at –15 °C, deaths from gallery collapses, and suicides from despair. Ilias Kajo, sentenced to eight years for “agitation and propaganda,” recounted: “The wake-up bell rang at 5. After roll call at 6 we left the camp and climbed the mountain, walking an hour and a half to reach the galleries. There we greeted each other with the phrase ‘Mirëdalsh!’—because we might never come out alive.” Political prisoners in this camp were treated as a labor machine. Their work generated significant revenue used by the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Finance for investments. Work ran in three shifts, the first starting at 6:30 and the last ending at 22:30. Food was scarce; it was considered a festive day when beans were served, and dinner ended with tea and a small piece of bread. Medical care was inadequate and hygiene conditions were alarming.

The working group established by Order No. 22, dated 06.02.2023, of the Chair of the Authority, for the organization of commemorative activities on the 50th anniversary of the Spaç Revolt, produced over 50 audio-visual testimonies of survivors of imprisonment in Spaç and of the relatives of those who were executed.

Much has been said about Spaç over the years. Well-known figures of the time have given testimonies, such as Visar Zhiti, poet and former minister; Fatos Lubonja, publicist and media activist; and painter Maks Velo. But AIDSSH went further, expanding the circle of witnesses. Their voices, silent until yesterday, are now part of history. The questionnaire prepared by AIDSSH experts helped secure authentic testimonies from this camp.

The following interviews speak of the hard labor, cruel treatment, reasons for the revolt, family solidarity and endurance, the children’s interrupted dreams of education, the stigma of being labeled “enemy of the people,” and the meaningful hope that the remains of missing family members will one day be returned home.

Gëzim Çela was only 21 years old when he was arrested “for attempting to escape.” He recalls that he worked beyond the quota. “If you only met the quota, they’d punish you. I had to load four wagons of pyrite per day, otherwise the punishment cell awaited me.”

Musa Hoxha, sentenced “for agitation and propaganda” at the age of 21, worked in the most difficult zone of the mine, Zone 2, without technical safety measures and in temperatures of 45–50 degrees Celsius. “Often, when I couldn’t meet the quota, they would chain me for two to three hours to a post in the snow. In one of these punishments, the irons burst my veins, and I fainted. After that, I did everything possible to meet the quota because I could not endure the punishment cell, or being chained to a post. The punishment cell was terrible. Two to three square meters, only with socks, they would strip your coat and wool sweater. You were given a blanket only at 7 a.m.”

Ilir Malindi, sentenced at age 20, recounts: “I, as a miner, worked in the second zone, in the pyrite area. Pyrite is the material used to produce sulfuric acid; one wagon of pyrite weighs 2 tons. We had to extract four wagons per person, meaning 6 tons per person.

We were organized in groups of three, tasked with moving about 20 tons of material outside. Pyrite has a property that generates high heat when reacting with water and moisture, so the temperatures at the workplace reached 45–50 degrees Celsius.

From 45 degrees inside, you went to –15 degrees outside to unload the material. Outside, it was freezing, and you had to do this work during the day. If the quota wasn’t met, they had a saying: ‘meet the quota or your soul!’ Not meeting the quota meant the punishment cell.”

Shkëlqim Abazi was only 16 when he was sentenced. “The Spaç revolt was not spontaneous; there had been 30 years of uninterrupted violence—it was bound to explode. Before the revolt erupted, it was Sunday. Many political prisoners didn’t want to go to work because legally Sunday was a day off,” Abazi recalls.

Gëzim Çela, a former prisoner, explains that the prisoners initially shouted slogans against the hard labor in the mine, which then evolved into political cries such as: “Down with communism!”, “Long live Free Albania!”, “They’ve dressed us in black, mother!”, “We want Albania like all of Europe!”

Napoleon Gumeni was 10 years old in April 1970 when his father, Izet Gumeni, was arrested and sentenced to 25 years for collaboration with gangs: “I won’t forget. I was 14. Along with my younger sister, we arrived around two in Spaç. The police wouldn’t let us see our father that day, telling us he was at work. We slept behind a barrack of the command, beaten by the cold wind of the Spaç gorge.”

Menduhije Pojani, daughter of Njazi Bylykbashi, a former prisoner “for agitation and propaganda” who served time in Spaç, says: “After my father’s imprisonment, my mother had to raise four children. She worked all day in agriculture, carrying wood on her back to warm and feed us. Our elderly grandmother helped as well.”

Lirie Alibali, wife of Ylli Alibali and sister-in-law of Xhevat Alibali, former prisoners accused of “agitation and propaganda,” recalls: “After my husband’s arrest, all doors were closed to me. No one wanted to deal with me. Relatives told me: ‘You came today, don’t come again!’ People avoided me and took different paths because I was stigmatized. I couldn’t separate my daughters from their father. I accepted my fate.”

Ioann Çeli was 16 when his father, a soldier, was arrested for “violent acts against the people’s power”: “After my father’s arrest, my older sister, who studied at the Faculty of Philosophy in Tirana, was expelled from school in a ceremony. They demanded she be publicly shamed in front of the school.”

Leonard Bejko was only 5 when his father, Dervish Bejko, executed in 1971 for “attempted escape,” was shot. He is one of the prisoners executed during the Spaç Revolt of May 21, 1973: “I have a void without my father. I buried him in Pogradec in memory of him. When I visit, I light a cigarette. But for whom? There are no remains. I light it to the earth, to the cold marble.”The testimonies collected, carefully administered, will be made available to researchers at any time, under the regulations of Albanian archives and the consent of citizens who entrusted their stories, via an agreement signed with the interviewer. The AIDSSH undertakes to manage and preserve these recordings with the standard of a valued historical archive.

The twenty selected interviews are valuable resources for scientific research, complementing archival documents and highlighting events deliberately neglected in the official documents of the former State Security.

Alongside the challenges of rewriting our dictatorial past, these testimonies hold exceptional value, as biological time moves on and the risk of forgetting becomes ever more present.

Within the framework of academic studies on forced labor during the dictatorship, and considering the recurring need for history to be rewritten and never receiving a final seal, shedding light on the Spaç prison-camp adds archival and historical sources that help Albanian society understand the oppressive and dehumanizing mechanisms the state employed between 1944 and 1991.

The primary source for this publication was the AIDSSH archive, containing documents from the file of the “Object of Special Importance of Unit 303, Spaç,” as well as investigative and judicial files of the prisoners held there. The publication was further enriched by oral archives, which, although considered secondary sources, are equally important because they offer living testimony. These serve as a call for reflection for contemporary society, which must not repeat the mistakes of the past.

The Authority further deepened its work toward creating the archival collection, adding documents from the former State Security to other official documents obtained through institutional cooperation. From holding a technical roundtable, data were obtained from the expertise of professors and mining engineers who had worked during that period in the sectors and galleries where Spaç prisoners had also been active.

Contribution

The testimonies and information obtained through communication with local institutions placed AIDSSH before new facts regarding the bodies of individuals killed or who died while serving their sentences in Spaç prison.

Research conducted in institutional documents, such as those of the General Directorate of Prisons, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the General Directorate of Archives, confirmed that a portion of former prisoners—executed, killed, or deceased due to hardship, illness, work accidents, or escape attempts during their sentences—still do not have a grave.

Based on these findings, the Authority initiated administrative investigation procedures to verify the suspected burial sites and determine the fate of 44 missing persons. This included collaboration with local authorities to protect the sites from tampering, as well as cooperation with law enforcement institutions to recover the remains of those killed or deceased while serving their sentences in Spaç prison.

The disappearance of graves, as observed, was employed by the regime for two purposes: not only to silence opponents and critics, but also to create insecurity and fear among others, compelling them to remain silent and refrain from challenging the authorities.

The publication emphasizes that the disappearance of bodies constitutes a violation of fundamental human rights as declared in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The victims also include their families, who spend the rest of their lives seeking information about the missing.

The publication provides a report on the progress of the administrative investigation into the 44 missing individuals from Spaç prison, as well as an overview of the activities AIDSSH has carried out in commemoration of the anti-communist revolt in Spaç.

The Importance of Preserving Collective Memory of These Traumatic Events

Preserving collective memory of these tragic events is becoming increasingly important for the democratic future of the country. A lack of understanding of the past risks leaving gaps in social culture as well as in policymaking and governance. Meanwhile, public, institutional, and educational spaces remain underinformed about several aspects of the dictatorial regime.

The fall of the communist regime in Albania was not accompanied by a thorough investigation of the crimes committed during its rule, nor were the perpetrators ever seriously held accountable or publicly asked for forgiveness from the victims of the communist genocide. To this day, these events are largely absent from official history curricula. Experts note that avoiding discussion of serious human rights violations against various groups—or other sensitive topics from this period—remains a challenge. Despite numerous projects aimed at improving history education in schools, critical thinking, historical empathy, and multiple perspectives have not yet been sufficiently encouraged.

To promote historical knowledge and preserve collective memory, the Authority has published specialized works on the Spaç revolt, including texts for school-age audiences written by children’s authors and supported by the academic expertise of leading historians of the period.A children’s book and an adapted film about the event and its history are part of the educational platform “Të “Learning from the Past—Open Educational Resources 1944–1991,” designed to assist teachers of history, civic education, philosophy, language, and literature in conveying this historical event to students in the pre-university system.

Through this ensemble of media, educational, and instructional productions, the aim is to transform the resonance of this historical event into a symbolic day of remembrance for society. It also seeks to inspire further acts of reflection, including the rehabilitation of all former prisoners and the transformation of the Spaç prison camp into a collective memory museum, to commemorate the crimes committed there against human life and dignity..

For the completion of this publication, I would like to thank the dedicated work of all AIDSSH staff across its various directorates. The questionnaire format was developed by the Directorate of Scientific Support and Civic Education. Transcriptions were carried out in the offices of AIDSSH, and the recorded audio-visual testimonies were processed by the audiovisual sector. The archival document collection was compiled and processed by the Directorate of Archives.

I would like to thank the Directorate of Inter-Institutional Relations in the Process of Identification and Recovery of Missing Persons for their role in communicating with former prisoners for the interviews, as well as for their fieldwork in conducting administrative investigations regarding the missing individuals in Spaç.

I also extend my gratitude for their expertise to the professors and mining engineers, including Dr. Viktor Doda, former Minister of Energy and Mines and former engineer in this mine; Prof. Dr. Kimet Fetau, lecturer in Geology and Mining; the economics expert Fran Gjergji from “Albakër”; and Dr. Femi Sufaj, researcher and Deputy General Director of Prisons.

This work has been extensive and meticulous, and I thank all contributors. I especially express my gratitude to the survivors of the Spaç prison and of prolonged internments, as well as their families, who, despite their age, health conditions, and emotional trauma, expressed willingness and collaborated to provide their testimonies. These accounts are extremely valuable and irreplaceable for documenting the revolt of prisoners in Spaç on May 21, 1973, as well as the inhumane treatment and harsh labor in the mine.

The totalitarian communist regime of Enver Hoxha, which ruled Albania after World War II until 1990, was characterized by: massive violations of human rights, individual and collective killings and executions (both with and without trial), deaths in labor and concentration camps, deaths from starvation, torture, deportations, forced labor, physical and psychological terror, genocide based on political origin or property inheritance, as well as violations of freedom of conscience, thought, and expression, press freedom, religious freedom, and political pluralism. Raising public awareness in Albania—particularly among the younger generation—about the inhumane crimes committed by Enver Hoxha’s dictatorial regime remains a continuing challenge for the country.

Revealing the history of the forced labor camp in Spaç confronts us with several unresolved issues, such as:

Lack of accountability. Even though 30 years have passed, there is still a lack of accountability for the crimes committed in that camp and within the forced labor system in general. Many of those directly responsible for these crimes have avoided responsibility and have not been punished.

Empowerment of the victims. Uncovering history gives survivors the opportunity to share their testimonies and reaffirm their identity as victims. This is a way to regain control over the narrative and to help in the healing of psychological wounds.

Building a just society. The lack of accountability and justice to date shows that the process of building a just society remains unresolved. Uncovering history should serve as a step toward a comprehensive process of constructing a truly just society.

Lack of institutional memory. State institutions have shown a lack of will to uncover and preserve the collective memory of these events. This indicates that there is still a need to increase institutional responsibility and engagement in this regard. Ultimately, this uncovering of the history of Spaç demonstrates that we still have much to learn from the past, in order to build a just and democratic future, by fully confronting the truth of that time.

Bibliography

Decisions and Orders

AIDSSH, Order No. 22, dated 02.2023, by the Chairperson of the Authority, “On the organization of commemorative activities on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Spaç Revolt.”

AIDSSH, Decision No. 374, dated 02.06.2023, “On the initiation of an administrative investigation with the aim of clarifying the fate, locating, identifying, and recovering the remains of persons who died or went missing during their imprisonment in Spaç Prison.”

AIDSSH, Decision No. 724, dated 12.2023, “On the approval of the report regarding the administrative investigation aimed at clarifying the fate, identifying, and recovering the remains of prisoners who died or went missing during their imprisonment in Spaç Prison.”

Strategic Plan of the Authority 2023-

AIDSSH Archive

AIDSSH Archive, investigative-judicial files of prisoners and re-sentenced individuals for the Spaç revolt.

AIDSSH Archive, Fund: Branch of Internal Affairs Mirditë, file ORV 123 of Reparti No. 303 Spaç, 244 pages.

AIDSSH Archive, Fund: Branch of Internal Affairs Pukë, file on measures to be taken when prisoners escape from Spaç Reparti, 14 pages.

AIDSSH Archive, Fund No. 4, File 335: “Some conclusions from the revolt in Spaç camp,” 11 pages.

AIDSSH Archive, Fund 4, File No. 217: “On certain issues in the Laç Chemical-Metallurgical Combine and the Spaç copper mine,” 9 pages.

Fund: Directorate I of State Security, Branch 7, 1975, File 114: “Information sent to the Party and State leadership on damages, misuses, and other deficiencies in the industrial-mining sector.”

Fund: Branch IV, File 801: “Management files, heavy industry and mines.”

Fund: Branch IV, File 95: “Management files, heavy industry and mines,” Volume I.

Fund IV, File 95: “Management File, Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume II

Fund IV, File 95: “Management File, Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume III

Fund IV, File 95: “Management File, Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume IV

Fund IV, File 95: “Management File, Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume V

Fund IV, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume I

Fund IV, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume II

Fund IV, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume III

Fund IV, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume IV

Fund IV, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume V

Fund IV, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume VI

Fund IV, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume VII

P.B. Tirana Fund, File No. 173, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume I

P.B. Tirana Fund, File No. 173, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume II

P.B. Tirana Fund, File No. 173, “Management File: Heavy Industry and Mines,” Volume III

Academic References

Meta, Beqir. Analytical Overview of the Prison, Internment, and Forced Labor System During the Communist Regime in Albania. Denied by the Regime, AIDSSH, 2021.

Sufaj, Femi; Sota, Jeta. Life in Forced Labor Camps, from the Perspective of Official Reports. Denied by the Regime, AIDSSH, 2021.

Boriçi. Statement from the Political Bureau of the Party of Labour of Albania Regarding Violence Against Prisoners and the Interned by the State Security Organs Until 1953. Denied by the Regime, AIDSSH, 2021.

Pandelejmoni (Papa). Memory and Life Stories of Forced Labor Camps, Internments, and Prisons in Communist Albania. Denied by the Regime, AIDSSH, 2021.

Framework Study: On the System of Prisons, Internment, and Forced Labor During the Communist Regime in Albania with a Focus on Establishing a Memorial Museum at the Former Tepelena Internment Camp. AIDSSH, 2019.

Group of Authors. Political Persecution, Challenges of the Albanian Transition. Albanian Center for Trauma and Torture Rehabilitation, Tirana.

Group of Authors. A Short History of Education Unit 303 in Spaç-Mirditë, 1951-1991. Published by the organization Cultural Heritage Without Borders.

Dr. Gentiana Sula

Chair of the Authority for Information

on the Documents of the former State Security

Spaç in Digital Memory: 52 Years Since the Revolt

Today we commemorate the 52nd anniversary of the Spaç political prisoners’ revolt through the activity “Spaç in Digital Memory,” honoring a history that pains us, yet at the same time gives us extraordinary strength. This activity is not merely a remembrance; it is a programmatic step toward building a society that learns from the past, honors the victims, and works for justice.

Dr.Mirela Sinani

Legal expert at the Authority for Information on Former State Security Documents.

The Spaç Prison and Slavery of political prisoners

The European Parliament, in its resolution of 19 September 2019, emphasized the importance of European memory for the future of Europe [2019/2819 (RSP)] with “the aim of honoring the victims, condemning the perpetrators of crimes, and laying the foundations for a reconciliation based on truth and the work of memory.”

In the vast repository of human knowledge, humanity has long classified slave-owning systems as systems based on the enslavement of humans by other humans, where property rules extended even to people, who were bought and sold like any other commodity, as if they were mere objects—with the exception that these “objects” could speak, walk, and even have feelings (?!). Yet the history of human society is filled with centuries of enslaving people beyond the formal slave-owning systems. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the most advanced forces, inspired by the philosophical ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity, rose against slavery as a shameful stain on the face of humanity. With the abolition of slavery, they were aware that the shame of this tradition of enslavement would still have to be felt for several generations; and, as time passed, this shame would gradually fade until it remained merely a part of history. Political reality, however, quickly overturned this idea.

Communism, fascism, and Nazism—three totalitarian regimes that emerged in the heart of Europe in the 20th century—along with two consecutive world wars, severely challenged humanity and shook to its core the ideas and reality of freedom. Historically, communist totalitarianism appeared earlier, beginning with the proletarian revolution of 1917 in Tsarist Russia. After the Second World War, the communist system expanded its influence across all countries of Eastern Europe. The hatred and desire for revenge against those of a different race or nation abroad were replaced by hatred and revenge against the “other” here, within the country’s own borders, within the nation itself—against those of a different class than the proletariat, against those with thoughts different from Marxist ideology.

Such a totalitarian system violently seized power in Albania as well, striking at both the economy and society, and setting Albanians against one another. Albania, a country so small in both area and population, was subjected to a strict regime of continuous purges targeting people with ideas different from communist ideology or with origins outside the proletariat. Villages and regions were emptied of entire families and clans, and families were displaced and interned in labor and internment camps.

Among the many prisons, stretching from north to south and filled with Albanians of all ages, Spaç Prison stood out. If anyone thought that slavery was a notion belonging only to humanity’s distant past, or that it existed only in old films, they were mistaken. Slavery remained alive and was massively employed under the state of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Spaç Prison, also known as a labor camp was one of the prisons where political prisoners were exploited through forced labor. Officially, this prison bore the name re-educationcamp(?!) Të etiketuar si armiq, të përbuzur, të poshtëruar, të lënë në vetmi, pa familjarë, pa shokë e miq, pa askënd, të izoluar në një vend të shkretë mes malesh, të torturuar, të shfrytëzuar sa t’u dilte shpirti, të masakruar dhe poshtëruar edhe së vdekuri: këta ishin skllevërit e kohës së re, që figuronin vetëm në pasqyrat e realizimit të planit të prodhimit të minierave si fuqi punëtore, madje me një pagesë sa 10% e pagesës së një punëtori, kundrejt një shfrytëzimi të jashtëzakonshëm, që figuronin në listat e fuqisë punëtore për të ndërtuar uzinat e fabrikat dhe që torturoheshin për vdekje për çdo mosrealizim norme, që edhe vriteshin barbarisht, një fenomen i panjohur për pjesën tjetër të popullsisë, që nanurisej me iluzionet e propagandës komuniste mbi rezultatet e punëtorëve të minierave që tejkalonin planet, mbi rininë që hapte kanalet e mëdha kulluese, thante kënetat, ndërtonte uzina dhe fabrika, dhe lulëzonte atdheun.

Diktatura e proletariatit dhe lufta e klasave u përdorën nga partia në pushtet për të kultivuar frikën, për të hapur fushatat e “gjahut” njerëzor dhe për të siguruar skllevër për sektorët më të vështirë të ekonomisë. Të burgosurit e Spaçit ishin “gjahu” i shtetit komunist, më saktë i një partie të vetme që drejtonte tërë shtetin, ata ishin provokuar, shtytur në kurth dhe zënë nga shteti, ishin rrëmbyer, dhunuar, torturuar, dënuar dhe burgosur nga një shtet që vepronte me ligj, si një bandë kriminale kundër popullit të vet. Në Deklaratën e të Drejtave të Njeriut dhe të Qytetarit të vitit 1789, pikërisht dy shekuj përpara sesa shqiptarët “të zgjidhnin” shtetin e diktaturës së proletariatit, renditen të drejtat natyrore dhe të patjetërsueshme të njeriut: liria, prona, siguria dhe rezistenca ndaj shtypjes. Shqiptarëve u ishin hequr të tëra këto të drejta natyrore duke filluar nga viti 1944 e më tej, me një sërë masash e reformash ekonomike, megjithatë ata e konsideronin veten të lirë, sepse… ishin çliruar nga pushtuesi i huaj, konsideroheshin të lirë meqë nuk ishin brenda burgjeve?!

Në Deklaratën e të Drejtave të Njeriut dhe të Qytetarit të vitit 1789 përcaktohet se liria ka të bëjë me lirinë për të bërë gjithçka që nuk dëmton askënd tjetër; prandaj ushtrimi i të drejtave natyrore të secilit njeri nuk ka kufij, përveç atyre që sigurojnë anëtarët e tjerë të shoqërisë, gëzimin e të drejtave të njëjta. Këto kufij mund të përcaktohen vetëm me ligj. Ky konceptim për lirinë i deklaruar që në shekullin XVIII ishte hequr me ligj në Shqipërinë e diktaturës së proletariatit dhe, në çdo rast, institucionet përkatëse shtetërore mund të ngrinin akuza “për agjitacion e propagandë kundër shtetit”. Liria për të lëvizur lirshëm ishte zhdukur me kohë. Me pretekstin e rrethimit nga bota borgjeze, i gjithë vendi ishte i rrethuar me kufij të mbyllur me tela me gjemba dhe i ruajtur me roje të armatosura, gjë që dëshmonte kthimin e të Shqipërisë në një burg të përmasave gjigante.

Kushdo që dëshironte të shkonte në botën borgjeze, akt që nuk i shkaktonte dëm askujt tjetër veç vetes së vet, arrestohej për ‘‘tentativë arratisjeje’’. Edhe në këtë pikë, ligjet e shtetit të diktaturës së proletariatit bënin hapa mbrapa, duke rrëzuar Deklaratën e të Drejtave të Njeriut e të Qytetarit të shpallur në shekullin XVIII.

Edhe pse liritë ishin zhdukur njëra pas tjetrës- ishte hequr liria e shprehjes dhe e mendimit ndryshe, liria e lëvizjes së lirë – nën trysninë e propagandës dhe të frikës nga agresioni i huaj, shqiptarët kishin iluzionin se ishin të lirë. Kjo ishte drama e shqiptarëve. Pikërisht, në këtë atdhe “të lirë”, me këta shqiptarë “të lirë”, lulëzonte fenomeni i skllavërimit të njeriut nga shteti. Në fakt, të gjitha hallkat ishin qepur trashë, por gjithsesi, diktaturës i duhej një kuadër ligjor si justifikim, për farsën se po vendoste drejtësi.

Nga momenti që kundër dikujt ishte ngritur një akuzë, jeta e tij ishte shënjuar. Të burgosurit politikë ishin shpallur armiq: jeta e tyre nuk i interesonte më askujt, prandaj kalimi i portës së burgut i nxirrte ata nga dimensionet hapësinore- kohore të realitetit shoqëror. Shteti, në fakt, bëhej pronar i jetës dhe i vdekjes së tyre. Pavarësisht se dënimi mund të ishte edhe vetëm 5 vjet dhe me një akuzë qesharake, shteti sajonte pretekste për të dhënë ridënime të njëpasnjëshme dhe për të mos e lejuar më atë person të dilte i gjallë nga burgu, nuk e lejonte të fitonte lirinë pas kryerjes së dënimit, sikurse edhe mund ta asgjësonte pa dhënë llogari e pa mbajtur përgjegjësi askush, siç kishte ndodhur në shumë burgje, mes tyre, edhe në Spaç. Jo vetëm shfrytëzimi me punë të detyruar, në mënyrë çnjerëzore, por sidomos ndërprerja e çdo mundësie për rifitimin e lirisë përmes dënimeve të njëpasnjëshme, përbëjnë karakteristikat themelore të skllavërimit të të burgosurve politikë në burgjet e diktaturës në Shqipëri.

Ajo që ishte e veçantë për Spaçin, lidhej me shfrytëzimin e gjahut njerëzor për punë të detyruar në miniera, një nga sektorët më të vështirë të ekonomisë, me përfitime shumë të mëdha, por me rrezikshmëri të lartë jete dhe, për këtë arsye, me mungesë të madhe të fuqisë punëtore. Të burgosurit në burgun-kamp pune të Spaçit ishin të detyruar të realizonin me çdo kusht normën, përndryshe jeta e tyre varej në një fill: që shteti, përmes dorës së rojës, ushtarit, oficerit, policit, operativit etj., mund ta këpuste pa asnjë problem, sepse jeta e një “armiku” nuk vlente. Për të qartësuar sa të jetë e mundur, shfrytëzimin e të burgosurve në Spaç, nga qershori i vitit 1968 e deri në mars të vitit 1991, AIDSSH nisi një komunikim, bashkëpunim dhe partneritet me disa institucione shtetërore: me Ministrinë e Brendshme, Ministrinë e Drejtësisë, Ministrinë e Ekonomisë dhe Financave, Ministrinë e Infrastrukturës dhe Energjisë, me struktura vartësie të kësaj të fundit, si “Alb Bakër” sh.a, me Arkivin e Shtetit.

Pas këtyre komunikimeve, me disa prej institucioneve edhe në mënyrë të vazhdueshme, u krijua një tablo se çfarë ishte dhe çfarë solli dënimi me punë të detyruar brenda burgjeve të diktaturës, për qindra e mijëra shqiptarë, të cilët ishin gjykuar, shumica për arsye politike dhe për të cilët në gjykata ishte shqiptuar dhe shkruar vendimi, vetëm me heqjen e lirisë. Gjatë 23 vite të ekzistencës së atij burgu famëkeq vuajtën dënimin më shumë se 2200 të dënuar.

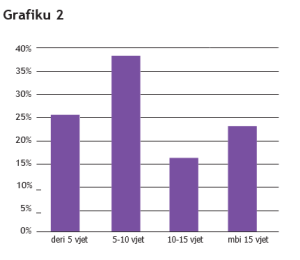

Në çdo vit, në burgun e Spaçit pati rreth 900-1100 të burgosur, 20% e të cilëve ishin të moshës 18 deri në 25 vjeç; 75% ishin të moshës 25 deri në 60 vjeç dhe 5% ishin të moshave nën 18 vjeç, apo mbi 60 vjeç.

Të dhënat janë pasqyruar në grafikun djathtas sipër:

Siç shihet edhe nga grafiku, pjesën më të madhe, rreth 75%, e zënë mosha 25-60 vjeç, mosha më e fuqishme për punë të rëndë.

Për nga dënimet:

- Të dënuar deri në 5 vjet heqje lirie, ishin rreth 25% e të burgosurve.

- • Prisoners sentenced from 5 to 10 years of imprisonment constituted about 38%.

- Të dënuar me 10 deri në 15 vjet heqje lirie, ishin rreth 15% e të dënuarve me

- • Prisoners sentenced to over 15 years of imprisonment constituted about 22%.

Të dhënat pasqyrohen në grafikun e mëposhtëm:

Në burgun e Spaçit, gjatë gjithë viteve, rreth 55% e të burgosurve ishin përsëritës, kurse një pjesë e të burgosurve ishin edhe të ridënuar po aty, gjatë vuajtjes së dënimit.

Një e dhënë shumë e ndryshueshme ka qenë origjina e të burgosurve, që hedh dritë mbi një fenomen shumë radikal siç ishte zhvillimi i luftës së klasave, përmasat, shtrirja, thellësia, ashpërsia e së cilës, në shoqërinë shqiptare, ishte e tillë që, prej saj, nuk përjashtohej askush. Lufta e klasave, që sipas orientimeve të Komitetit Qendror të Partisë së Punës së Shqipërisë, herë ulej e herë ngrihej, po asnjëherë nuk shuhej, paraqitej si burim zhvillimi, ngjashëm me përfytyrimet e zjarrit heraklitian, që përshkonte gjithçka. Mbështjellë me këtë veshje filozofike antike dhe sidomos bazuar tek ideologjia marksiste, lufta e klasave u përdor si arma që spastroi shoqërinë shqiptare dhe ndryshoi thellësisht fizionominë shoqërore, ekonomike, kulturën, të drejtën, zakonet, traditat, moralin, mendësitë dhe përjetimet psikologjike brenda një kohe shumë të shkurtër. Koncepti mijëravjeçar për lirinë dhe përvoja njerëzore e lirisë erdhi dhe u rrudh në një përfytyrim mjeran lirie, megjithëse i “argumentuar shkencërisht” dhe në një përvojë “lirie” që identifikohej me të menduarit e të jetuarit siç thotë partia dhe me të jetuarit si në rrethim. Ndryshueshmëria aq e madhe e origjinës së të burgosurve dëshmon edhe faktin tjetër që të dhënat që përdoreshin nga prokuroria dhe gjykata, si fakte për të ndërtuar akuzën dhe për të vënë dënimin, ishin subjektive

Statistikat tregojnë, gjithashtu, se numri më i madh i të burgosurve në raport me popullsinë, ka qenë nga zonat kufitare. Edhe pse kufiri shqiptar ishte një pjesë territori e rrethuar me tela me gjemba, me sinjalizues elektrikë, e ruajtur nga roje të armatosura që kishin të drejtë të vrisnin këdo që i afrohej dhe që ishin të mbështetur nga qentë e stërvitur të kufirit, të jetuarit pranë vijës kufitare bëri që tek ajo pjesë e popullit që banonte atje, më pranë pjesës tjetër të botës, të mbetej gjallë dhe të pulsonte vazhdimisht ndjenja e lirisë, ideja e lirisë dhe shpresa e shpëtimit nga ky shtet i vetërrethuar, që vetasgjësonte sistematikisht popullsinë e vet. Të dhënat e përgjithshme të realizimit të planit që përpiloheshin në çdo minierë, nxirreshin nga të dhënat e mbajtura në regjistra,ku në kolona të veçanta shënohej realizimi i normës ditore nga çdo i burgosur, i rreshtuar si fuqi punëtore në minierë. Trajtimi i secilit prej tyre, varej nga realizimi ose mosrealizimi i normës. Shprehja “O normën, o shpirtin!” e pambështetur në ndonjë vendim gjykate, e pashkruar në muret e burgjeve, por e shqiptuar nga të gjithë policët dhe rojet e burgjeve, duke ia përplasur në fytyrë çdo të burgosuri që kryente punë me detyrim, nuk ndryshon aspak nga shprehja “Puna të çliron”, e shkruar në hyrje të kampeve naziste të shfarosjeve në masë. Njëra shfaqej menjëherë dhe dukej që në hyrje, tjetra nuk dukej, por dëgjohej përditë, sa kohë kishe jetë në ato burgje-kampe pune, ndërsa pasojat e saj mbetën të fshehura e të panjohura për një kohë shumë të gjatë – mbi gjysmëshekullore.

Mosrealizimi i normës shoqërohej me dënime torturuese, deri në ridënime. Treguesit e realizimit të planit nga të burgosurit që punonin në miniera janë në rritje, me tejkalime çdo muaj e çdo vit. Përtej statistikës së thjeshtë dhe shifrave të ngurta, që gjithsesi, nuk tregojnë as kushtet teknike të minierave, as kushtet e punës së të burgosurve minatorë, as mjetet me të cilat punonin, as krimet e kryera mbi ta brenda minierave, kushdo mund të pyesë: Po ç’ishin këta të burgosur që punonin? Ç’ishin këta të burgosur që punonin dhe që dënoheshin për mosrealizimin e normës? Ç’ishin këta të burgosur që punonin, që dënoheshin dhe që torturoheshin për mosrealizimin e normës? Ç’ishin këta të burgosur që punonin, dënoheshin, torturoheshin dhe që vriteshin për mosrealizimin e normës? Ç’ishin këta të burgosur që punonin, dënoheshin, torturoheshin, vriteshin dhe që u zhdukej trupi pa gjurmë, maleve ose thellësive të minierave, për mosrealizim norme? Mbi bazë të cilit ligj, a të cilit vendim gjykate? Në çdo vend të qytetëruar të botës, në të drejtën penale, që nga përcaktimi i veprave penale e deri te përcaktimi i dënimeve, llojet dhe masat e tyre, qëllimi është që të parandalohet kryerja e një vepre penale, të ndëshkohet personi që e kryen, duke iu hequr, apo kufizuar liria dhe disa të drejta të tjera, si edhe të edukohet me qëllim rehabilitimin në jetën shoqërore, pas kryerjes së dënimit. Mënyra sesi ishte ndërtuar e drejta penale, qëllimi, konceptimi i veprës penale dhe zgjerimi tej mase i saj, pastaj i gjithë sistemi i institucioneve të përgjimit, zbulimit, ndjekjes, hetimit, gjykimit si edhe sistemi i institucioneve të vuajtjes së dënimit me burgje-kampe pune si ai i Spaçit e të tjerë, na jep pamjen e një shteti bandit i interesuar të shtyjë në krim, të rrëmbejë dhe të kriminalizojë sa më shumë njerëz, të dënojë sa më rëndë e të krijojë pretekste për të ridënuar, me qëllim që i burgosuri të mos dilte më i gjallë nga burgu, na jep pamjen e një shteti që, të dënuarit në burgje nuk ishin atje për të vuajtur dënimin, ca më pak për t’u rehabilituar, por për t’u shfrytëzuar maksimalisht, si fuqi e gjallë e punës deri në vdekje, madje edhe për t’u asgjësuar.

Në burgun-kamp pune të Spaçit norma e ditës së punës së një të burgosuri që përfshihej në fuqinë punëtore të minierës si punëtor i pakualifikuar, thjesht punëtor kazme dhe lopate, që mbushte e shtynte vagonët me mineral, ishte nxjerrja e 8 tonëve mineral bakri në një turn. Puna ishte e organizuar me tre turne, kurse paga ishte përcaktuar me ligj sa 10% e pagës së një punonjësi në gjendje të lirë, për të njëjtën punë të kryer. Të burgosurit e Spaçit që u shfrytëzuan për punë të detyruar në nëntokën e Spaçit, në 23 vite kryen 88.388 (tetëdhjetë e tetë mijë e treqind e tetëdhjetë e tetë) metër linearë punime minerare. Çdo metër linear i ri në minierë është hapur vetëm nga të burgosurit. Ndër punët e tjera ishin mbushja e mineralit nëpër vagonë, shtyrja e vagonëve me mineral, nxjerrja në sipërfaqe etj. Të burgosurit nxorën nga nëntoka e Spaçit 2.8 milionë tonë mineral bakri1 (llogaritur për periudhën 1968 – mars 1991, kohë kur ka funksionuar kampi) dhe rreth 1 milion ton mineral piriti.

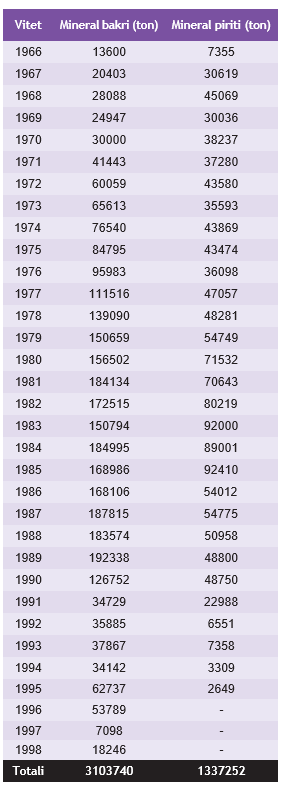

Në tabelën 1 janë paraqitur të dhënat zyrtare shtetërore, që sot i ka në zotërim Shoqëria aksionare “AlbBakër” sh.a. për prodhimin e mineralit të bakrit dhe të piritit në ish-minierën e bakrit, Spaç, në vite. Diferencat në sasinë e mineralit të nxjerrë në periudha të ndryshme, dëshmojnë edhe për shfrytëzimin që i është bërë punës së papaguar të të burgosurve, deri në vitin 1990.

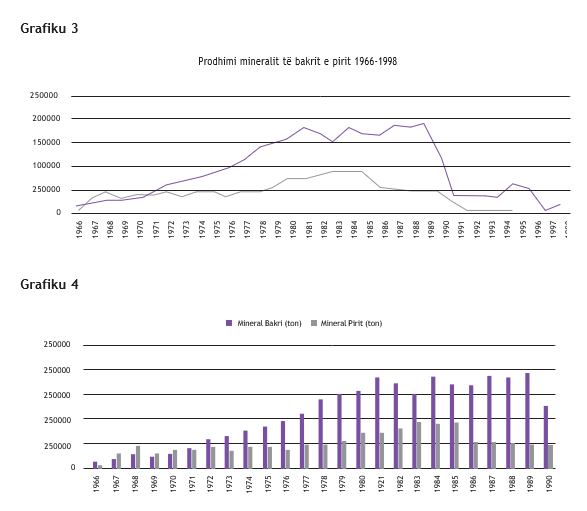

Në grafikun 3 paraqiten në mënyrë lineare, nxjerrja e mineralit të bakrit dhe të piritit, bazuar në të dhënat deri në vitin 1998. Nga viti 1966 e deri në korrik të vitit 1968, në minierën e Spaçit punonin vetëm punëtorë miniere. Siç shihet edhe nga kurba e grafikut, sapo aty pranë u vendos burgu i Spaçit, prodhimi i bakrit dhe i piritit u shumëfishua. Gjithashtu, me mbylljen e burgut të Spaçit në vitin 1991, shihet qartë edhe nga grafiku, se çfarë ndodh me prodhimin e mineralit të bakrit dhe të piritit: nxjerrja e bakrit ra në nivele minimale, kurse nxjerrja e piritit u ndërpre krejtësisht. Në grafikun 4 pasqyrohet prodhimi i mineralit të bakrit e të piritit krahasuar me njëri-tjetrin, çdo vit, deri më 1990. Nga minerali i bakrit, përqindja bakër e të cilit ishte rreth 1.15%,2 pas përpunimit u përftuan rreth 35 mijë tonë bakër, sasi kjo që në bursat e kohës, ku bakri kuotohej nga 1900 $/ton deri në 3500 $/ton, vlerësohej rreth 94 milionë e 500 mijë dollarë amerikanë ose krahasuar me bursën e sotme, pra viti 2023, ku bakri kuotohet rreth 8890 $, vlera do të ishte 311 milionë e 150 mijë dollarë amerikanë.

Produkti i mundit të punës së detyruar të të burgosurve i jepte frymëmarrje shumë sektorëve të ekonomisë. Sasi të mëdha të mineralit të bakrit shkonin në Uzinën e Telave në Shkodër, ku prodhoheshin produkte të rëndësishme për industrinë energjetike dhe mekanike. Një sasi e konsiderueshme sidomos bakër elektrolitik, eksportohej, shitej në tregje, apo shkëmbehej me klering me shtete të ndryshme në Europën Lindore dhe në këmbim merreshin makineri bujqësore, pjesë këmbimi, artikuj të ndryshëm industrialë, etj. Raportet financiare të këtyre transaksioneve është shumë e vështirë të gjenden, pasi në sistemin e diktaturës së proletariatit mungonte transparenca dhe çdo gjë zhvillohej e mbyllur dhe në fshehtësi. Edhe nëse mund të ekzistonte ndonjë dokument, p.sh., në Ministrinë e Tregtisë së Jashtme është zhdukur gjatë ndryshimit të sistemit dhe largimit të qeverisë që lidhej me atë sistem.

Minerali i piritit i nxjerrë në minierën e Spaçit, në sasi të përgjithshme, prej 1.211 154 tonë3 kryesisht shkonte për eksport, ndërsa një pjesë përdorej në Uzinën e Superfosfatit, ku prodhoheshin plehrat kimike për bujqësinë, si edhe shërbente si lëndë e parë për prodhimin e acidit sulfurik (H2SO4), etj.Shumë prej të burgosurve që kryenin punë të detyruar në miniera, të lodhur nga torturat dhe poshtërimet, në dëshpërim e sipër, hidheshin mbi telat me gjemba që rrethonin burgun-kamp pune të Spaçit, që s’mund të kapërceheshin e nga ku s’mund të arratisej askush, megjithatë rojet qëllonin mbi ta dhe i vrisnin.

Shumë të tjerë vdiqën nga mundimi, torturat, sëmundjet e mushkërive dhe sëmundje të tjera që merrnin nëpër biruca dhe në dhomat e tejmbushura me të burgosur e pa kushte jetese, si edhe nga mungesa e sigurisë teknike në galeritë e minierave, apo nga dhuna e ushtruar prej rojeve edhe gjatë procesit të punës.

Pjesa më e madhe e të burgosurve morën ridënime, duke i kthyer dënimet e tyre fillestare disavjeçare, në dënime thuajse të përjetshme. Të mbijetuarit nga burgjet komuniste dëshmojnë se shteti i diktaturës së proletariatit i kryente torturat sipas manualeve që i kishin ardhur nga Jugosllavia, Bashkimi Sovjetik apo Gjermania etj. Siç dëshmojnë të mbijetuarit, prifti katolik Pjetër Meshkalla kishte kundërshtuar përkthimin, nga gjuha gjermane, të manualeve me tortura çnjerëzore. Megjithatë, sistemi kishte në shërbim njerëz të specializuar në vendet komuniste për tortura, si edhe manuale që u përkthyen dhe aplikoheshin mbi të dënuarit.

Shfrytëzimi i të dënuarve për punë të detyruar në miniera, kushtet e vështira të punës, norma tepër e lartë dhe ndëshkimet e rënda për mosrealizimin e saj, mungesa e çdo mbrojtjeje teknike në punë, ushqimi shumë i pakët dhe jashtë standardeve shëndetësore, dhuna e vazhdueshme nga policia dhe punonjës të tjerë të shërbimit në burgje, ishin faktorët që shkaktuan shpërthimin e revoltës në 21 maj të vitit 1973 në Spaç, revoltë që zgjati tri ditë dhe tronditi nga themelet gjithë shtetin diktatorial. Të mbijetuarit nga burgu i Spaçit dëshmojnë se jo vetëm që kërkesat e tyre të drejta nuk u morën parasysh, por shteti i diktaturës së proletariatit reagoi me egërsi për ta shtypur revoltën. Me urgjencë u mobilizuan korpuse të tëra dhe u zëvendësuan ushtarët me trupa policore. Kishte aq shumë trupa në rrethim, saqë policët rrinin ngjeshur sup më sup. Që shfrytëzimi i këtyre skllevërve të socializmit të vazhdonte i pandërprerë, shteti veproi me shpejtësi, duke arrestuar të gjithë pjesëmarrësit më të parë dhe më aktivët në revoltë.

Në Spaç u zhvilluan gjyqe farsë dhe u dhanë dënime me vdekje, për katër nga pjesëmarrësit në revoltë, të cilët, u masakruan dhe ndoshta, disa e dhanë frymën e fundit, përpara se ajo të mbyllej plotësisht dhe shumë më parë sesa të zhvilloheshin gjyqet për ta.Tragjikisht, një pjesë e të burgosurve politikë të Spaçit edhe pas vdekjes mbajnë ende vulën e armikut për shkak se janë dënuar duke u cilësuar

për “akte terroriste”. Qindra të tjerë, e ndoshta më shumë, janë të dënuar pafundësisht të humbur e të pavarrë, sepse në mënyrën më mizore dhe në kundërshtim me çdo kod moral, që nga kohët më të lashta, trupat e tyre janë hedhur maleve dhe përrenjve gjysmë të groposur ose janë lënë në natyrë, që të shqyheshin nga egërsirat. Eshtrat e tyre s’dihet as ku ndodhen, as si të identifikohen. Diktatura e proletariatit s’kishte të ngopur me torturat ndaj trupave të të gjallëve dhe gjymtimet e trupave të të vdekurve, me zhbërjen e dinjitetit njerëzor, depersonalizimin, zhdukjen e varreve.

Ish-burgu i Spaçit ose burgu-kamp pune do të jetë përherë një vend i krimit komunist, krim që u krye në mënyrë masive dhe për gjysmë shekulli rresht, nga një sistem që, përmes propagandës, mashtroi popullin me pamje të bukura të lirisë dhe të jetës së lumtur, ndërsa e rrethoi të gjithin me klone dhe tela me gjemba, për të mos lejuar askënd as të ëndërronte të largohej për diku tjetër, as të shprehte ndonjë dëshirë të tillë.

Kushdo që, qoftë në mënyrë naive, e shprehu një ëndërr të tillë, qoftë që guxoi të provonte të kapërcente telat me gjemba ose ra në kurth dhe nga frika u drejtua nga kufiri me tela me gjemba, u dënua nga shteti i diktaturës së proletariatit, jo thjesht me burgim, por iu nënshtrua një procesi të mohimit tërësor shoqëror, për së gjalli si të vdekur, kurse për së vdekuri, të humbur e pa asnjë shenjë.

Sot në Spaç ende kemi një krim të vazhduar. Janë të zhdukurit, rreth 50 ish-të dënuar të identifikuar gjer tani që presin t’u prehen eshtrat aty ku duhej të ishin, pranë të afërmve të tyre, prej të cilëve u ndanë dhunshëm së gjalli. Çdo jetë vdes dhe jetë të lindura prej saj vazhdojnë, por vdekjet e Spaçit janë ndryshe, janë vdekje që jetojnë…Ndaj, Spaçi ka qenë një ferr dhe sot është një histori e rëndë edhe për t’u lexuar, një histori që i bën me turp shqiptarët dhe shtetin shqiptar, dhe detyron ndjesën ndaj të gjithë atyre njerëzve dhe familjeve të tyre, ndjesën ndaj brezave të rinj, për tronditjen që shkakton zbulimi i këtyre krimeve. Revolta e Spaçit do të mbetet në historinë e kombit tonë si një frymëmarrje shprese dhe besimi, nën dhunën e pandërprerë të diktaturës.

Jo rastësisht, Asambleja Parlamentare e Këshillit të Europës, në një rezolutë të veçantë, Rezoluta 1096, që në vitin 1996, theksonte se trashëgimia e regjimeve totalitare komuniste, nuk ishte një çështje e lehtë për t’u trajtuar: “Në planin institucional, kjo trashëgimi përfshinte centralizimin, militarizimin e institucioneve civile, burokratizimin, monopolizimin…; në nivelin e shoqërisë, shkonte nga kolektivizmi dhe konformizmi në bindjen e verbër dhe në mënyra të tjera të mendimit totalitar. Në këto kushte është e vështirë të ringrihet një shtet i së drejtës i civilizuar dhe liberal – prandaj strukturat dhe mënyrat e të menduarit të së kaluarës duhet të çmontohen dhe të kapërcehen”.

Hapja e dosjeve të shërbimit sekret do të ishte një hap, krahas hapave të tjerë – rehabilitimit të të gjithë ish-të dënuarve, ruajtjes dhe kthimit në vende të kujtesës kolektive të burgjeve dhe të institucioneve të tjera ku janë kryer krime kundër jetës njerëzore dhe dinjitetit njerëzor – që përmes njohjes së të vërtetës, të zhduken iluzionet për sistemin komunist dhe brezat e rinj të orientohen drejt ndërtimit të perspektivave të tjera shoqërore ku jeta njerëzore, ashtu siç na mësojnë filozofët që nga thellësitë e kohës e siç e ripërsërit Kanti, të trajtohet si qëllim e jo si mjet. Ndërmarrja e këtyre hapave do të shërbejë për ngrintjen e shtetit të së drejtës dhe mosdështimin e procesit të demokratizmit.

Ndryshe, siç theksohet në rezolutën 1096 të Asamblesë Parlamentare të Këshillit të Europës, “do të shikojmë të instalohet oligarkia në vend të demokracisë, korrupsioni në vend të shtetit të së drejtës dhe kriminaliteti i organizuar në vend të të drejtave të njeriut. Në rastin më të keq, do të asistojmë në “restaurimin e mëndafshtë” të një regjimi totalitar, qoftë edhe të përmbysjes me forcë të demokracisë ende në lindje e sipër”.

Mblodhën dhe përpunuan të dhënat:

Luan Ismaili, Anton Dukagjini, Vojsava Delilaj

Jonida Dervishi

“Legal expert at AIDSSH”

“Court rulings on the prisoners of Spaç”

The court decisions sentencing all those who served time in Spaç Prison, including re-sentencing decisions while serving a prior sentence in Unit No. 303, testify today to a history of extreme restrictions on the freedom to think and express oneself—up to the total annihilation of that freedom. Along with it, other liberties and rights were also restricted, in some cases even the right to live. What immediately emerges from the investigative and judicial files of those who served their sentences in Spaç Prison is the dominance of convictions for the crime of “agitation and propaganda.” Among approximately 30–40 sentencing decisions issued between 1957 and 1981, the criminal offense of “agitation and propaganda” appears in at least 20 decisions, resulting in around 75 sentences. Of these, in 8 judicial decisions issued between 1973 and 1981 against persons who were executed in Spaç while serving a prior sentence, all included the charge of “agitation and propaganda,” and 44 defendants were found guilty, primarily or among other charges, of this offense. Familiarity with these decisions sheds light on an anti-freedom-of-thought and anti-expression worldview, which in a system opposed to freedom permeates everything: from criminal policy and penal legislation, to the harsh sentences imposed for acts of “agitation and propaganda,” their practical application inside and outside prison, the lack of separation of powers, a politicized judiciary that acted not as a guarantor of human rights and freedoms or as a forum for objective evaluation of facts, but as a defender of the party’s ideological line; judicial decisions that effectively “ratified” the annihilation of this freedom; unilateral, politicized, non-objective, disproportionate reasoning, full of ideological indoctrination and partisan-patriotic rhetoric; the standards of proving and establishing facts, which largely consisted of thoughts and words; and the extreme disproportionality bordering on absurdity, attributing social dangerousness to authors for acts committed with thoughts and words.

The positioning and bias of the judiciary become evident in the ubiquitous phrases “our party/to our party” and those referring to “illuminating lessons from the party” or “as the party teaches us.” The judiciary considered it its duty to exercise “revolutionary vigilance” and to “carry out the class struggle with force and without interruption, until the final victory.”

There are also expressions that highlight what the judiciary, a priori, considered to be right (and, consequently, what is considered wrong as unjust), such as: “he has spoken against the correct Marxist-Leninist line… He has spoken against our democratic system and has said that there is no freedom or democracy here.” Or: “being old enemies of the party, the people, and our state, politically degenerate individuals with pronounced hostile tendencies against the dictatorship of the proletariat in Albania.” Or: “They have carried out hostile activities, both savage and cynical… deliberately counter-revolutionary… they have denied the colossal progress made in our country, such as in industry, agriculture, and other branches of the economy, and consequently, the unprecedented improvement of the welfare of our working masses…”

The court rulings testify to the “normalization” by the communist regime of the absurd and its enactment through the judiciary. They appear to reveal and represent the worldview of a regime—one fundamentally opposed to freedom of thought and expression. It did not tolerate the very existence of dissenting opinions, even attributing to them a high level of social danger. The consequences for people’s lives, from these processes—entirely devoid of the guarantees of a proper legal procedure by today’s standards—consisted of prison sentences of several years, sometimes multiple re-sentences adding many more years, alongside additional punitive measures, and in some cases, even the death penalty. These demonstrate a regime that built an entire system to annihilate freedoms, maintained itself through the suppression of free speech, and appeared most fearful precisely of free thought and expression.

Illustrative of this are: the criminal provisions on agitation and propaganda; the high number of convictions and re-sentences under this charge; the severity of the penalties prescribed for this offense; judicial reasoning that often cited the words or writings of the defendants, combined with harsh punishments for thoughts and speech, including even the right to hope for change; as well as those parts of judicial reasoning imbued with ideological pathos in defense of the Party and leadership, including unethical, insulting, and dehumanizing labels applied to defendants, wholly inappropriate for judicial language. These elements, among others, also reflect the worldview, professional capabilities, and judicial ethics of the time. All of this highlights, beyond the visible and statistical, and approaching the absurd, hallucinatory, and even laughable from the perspective of contemporary standards, human rights, due process, and the understanding of reality and indisputable truths, a pervasive and terrifying fear—ever-present among everyone, including the judges themselves—of truth, free thought, and free speech.

With a harsh penal policy and legislation, and a judiciary that was politicized and protective of party ideology, it appears that what is thought, said, or written by defendants—besides being considered sufficient grounds to bring someone to trial and punish them severely—is not subjected to any objective assessment of: (a) whether it could be true, even if undesirable to the leadership; or (b) whether there exists a real possibility that, through thoughts, ordinary communications, or exchanges among ordinary people, outside or inside prison, under conditions of imprisonment, words, writings, or poems could achieve goals or cause any concrete consequences in terms of “weakening the people’s power,” “undermining the power of the Party and the people,” “extending hostile activities in directions of foreign and domestic policy,” etc.

By the very nature of these decisions, it appears that the basic standard of judgment is such that reality and truth are considered “unreal” or “fabricated,” and the opposite as true. Accordingly, judges deem as unreal, false, or fabricated any words from defendants that: speak of a better life in capitalist countries; highlight the benefits of private property; fail to recognize—or worse, deny—what the judiciary sees and acknowledges as major achievements in all areas of welfare; point out deficiencies in the system and in rights and freedoms; document the suffering of the people or peasantry, the disruption of relations with other states, or the shortage of food items in stores; or assert that the system is not democratic.

The judicial decisions show that judges considered as true and within reality: the colossal achievements in all fields; the unprecedented welfare of the people in our democratic system; the enlightening lessons from the Party. They exalt the Party’s teachings and, sometimes, highlight the possibility of “re-education” and the right to work, which the Party allegedly grants even to “enemies and their families,” while at the same time threatening them with its “sharp sword,” depending on the stance of the “enemies.” With extreme pathos, alongside the Party lessons, the judiciary does not hesitate to evoke the people and Albanian mothers in party glorifications and in attributing the dangerousness of acts and their authors. The analysis of the elements of criminal acts is inadequate. Regarding the objective elements, it seems that the actions and facts leading to conviction consist of thoughts and words, which are subject to assessment based on the judges’ ideological stance. Assessment of the subjective elements, such as intentions and exaggerated aims, is unrealistic and appears unreasonable. The elements are generally proven through statements of the defendants, co-defendants, and witnesses before the investigation and trial. The decisions reflect the indictments (which are more detailed in describing and analyzing the facts). They are always upheld by higher courts. Simply thinking or speaking differently, or opposing anyone, with anyone, anywhere, as clearly emerges from these decisions, is unequivocally equated with hostile activity deserving the harshest punishments. Thus, one could end up in Spaç if the act of “agitation and propaganda” was committed by praising life in capitalist countries, mocking leaders, failing to recognize the “great victories of the Party,” or “dreaming of going abroad.” Or by expressing opposition to the Marxist-Leninist line, sympathizing with life in the West, speaking about freedom and rights in these countries, and showing disapproval of domestic television programs. One could be re-sentenced while serving a sentence in Spaç for the act of “agitation and propaganda” committed through words that noted the disruption of relations with other states, or by expressing personal opinions about what could happen in these directions; expressing disapproval of collectivization and saying that life is better through private property, stating that there is more abundance in capitalist countries compared to Albania, where people suffer from low incomes and stores are empty; or expressing opinions on the stance of the Albanian government regarding Kosovo, or showing disapproval of livestock herding practices.

In the verdicts against those involved in what is known and commemorated as the “Spaç Revolt,” alongside the charge of “agitation and propaganda,” the sentences also include the offenses of “terror” and “participation in an organization against the people’s power with the aim of committing the crime of economic sabotage.” While similar reasoning is evident regarding the first charge, which is generally “consumed” through words and slogans, for the other serious offenses there is no genuine analysis of each element of the criminal act, no objective assessment of the facts, the available means, or the concrete possibilities for achieving the alleged aims.

The analysis of court decisions helps to view and assess the judiciary of communism through its own words. The judiciary, in its own words, appears as part of a system without separation and balance of powers and, overall, without balance; as a politicized judiciary defending the party’s ideological line; with disproportional reasoning and pathetic ideological refrains; with lack of objectivity and extreme bias in judgments; with no guarantees for the accused and no defense; with poor assessments; indoctrinated and using language unsuitable for judicial decisions. The judiciary, in its own words, emerges as an important link in maintaining a dictatorial regime. It also appears as an enforcer and embodiment of a worldview opposed to freedom of thought and speech, and as an executor of every other liberty. It remains important to study and analyze the judiciary of communism as we aim for concrete results in the effective application in practice of the highest standards of human rights and due process, as provided today by the Constitution of the Republic of Albania, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights.

Others:

Imagine those men! In brown uniforms, poorly fed, poorly clothed, living in misery. Cursed men who do not see their families, who cannot caress their children, and who are often themselves almost children. Working underground, punished underground, seeing only earth. Imagine those men, smeared with the mud of the mine, pulling wagons of copper and pyrite and given only a plate of soup to eat. They are slaves.

Even if they achieved 100% of the work quota, they received only 10% of the wage of a miner working in free conditions.

A study by the current deputy director of prisons, Femi Sufaj, on the punishment systems under the dictatorship, highlights that the quota target was set as high as 225%. In this case a simple imprisoned worker received 35% of the wage for the work performed. If the quota was exceeded beyond this limit, the payment did not change. For those who did not achieve 100% of the quota, the payment was calculated in inverse proportion, meaning it was reduced.

“In 1972, with Decision of the Council of Ministers (DCM) No. 152, DCM No. 120 of 9 September 1968 on the remuneration of prisoners’ work was amended. Payment for prisoners who worked was reinstated at up to 15% of the wage set for the same work. There were also some improvements in the food diet, increasing by 100–160 calories through the inclusion of vegetables. Nevertheless, based on data from the Institute of Hygiene and Prophylaxis, the calories received by a prisoner were far below the minimum recommended values,” writes Sufaj in the book The Punishment System in Albania during the Communist Regime (1945–1990).

MILLIONS THE STATE EARNED FROM THE PRISONERS

It is noteworthy that the labor of prisoners generated considerable revenue for the state budget, which was later used not only for the needs of the Ministry of Interior but mainly by the Ministry of Finance for investments in other sectors. Sufaj reviews several reports on the economic balance of income created by prisoner labor and emphasizes that they carried out the country’s hardest work and were a key factor in increasing revenue.

“In 1948, income from prisoner labor was reported at 10,780,420.50 lek at the exchange rate of the time. During 1950, 16,000,000 lek was reported,” notes Sufaj. Only from Spaç, according to Femi Sufaj, the Albanian state secured in 1979 the sum of 3,537,001 lek, while in 1981 the sum of 2,193,984 lek. In the case of the draining of the Maliq swamp during 1950, 900 prisoners worked, completing 110,000 workdays and generating 12,671,741.50 lek in revenue; during 1951, 1,085 prisoners worked in this camp, completing 148,026 workdays and generating 22,773,449.65 lek in revenue, according to the Archive of the Ministry of Interior (Fund of the Department of Camps and Prisons, D.17, V.1951).

According to statistics calculated by the Authority of the Files, during the 23 years that Spaç functioned as a forced labor camp, 2,000 prisoners produced 2.82 million tons of copper and 1.3 million tons of pyrite, which translate into 2,500 kg of gold, says Gjergj Marku, a member of AIDSSH.

Engineer Halit Shqarthi notes that in 1969 the mine produced only 50 thousand tons of copper, while in 1981, with the increase in the number of prisoners, production rose fourfold to about 200 thousand tons per year.

A DOLL FOR THE DAUGHTER

Fatos Lubonja is perhaps one of the prisoners who best explained the camp’s routine. His description of workdays starting at 5 a.m. inevitably includes the quota. “They said material–bodies–holes. If you didn’t meet the quota you got the isolation cell as punishment, or you were kept chained outside, especially if you broke the rules.” When he was imprisoned, he left behind two daughters, the youngest only one month old. It was his mother’s letters, describing each week how the girls were growing, that kept him alive. “The work we did was unbelievable. Once I entered a competition in the mine and we made progress. We advanced so much that we exceeded the quota and I remember I earned 3,000 lek; with that I bought my daughter a doll. It was a competition, a work contest among the prisoners,” he recalls in testimony given to AIDSSH about Spaç.

GËZIM ÇELA, THE GUITARIST OF THE SPAÇ CAMP

At one time, the Spaç camp had a room the prisoners called the culture room. Gëzim Çela recalls that they had a friend from Fier who was a good mandolin player. “He told me, ‘Gëzim, find us a guitar, because with only a mandolin we can’t make music.’ When my mother came for a visit, I told her to meet the guitarist Medi Prodani and tell him that Gëzim wanted a guitar. He himself did not have a guitar and had told Vaçe Zela, whom I knew as a childhood friend.” Çela recounts that Vaçe Zela’s guitar eventually made its way to the camps where he was held.

It is almost legend that during the days of the revolt in the Spaç camp, the sounds of a guitar were heard. Former prisoner Gëzim Çela credits these sounds to Skënder Daja, a former prisoner and one of those executed as an organizer of the revolt. “At one moment, I remember Skënder Daja had climbed onto the terrace and taken my guitar, the guitar that Vaçe Zela had brought me.”

“The Party cared more for the cow barns than for the people.” This careless sentence spoken by Pal Gjergj Zefi from Rrushkull, Durrës, in his thirties, led to his imprisonment in Spaç for agitation and propaganda. It was 1973, the time of liberalization had ended. Pal Zefi arrived at the prison among the mountains, in an abyss where no trace of humanity could be felt. He began his ten-year sentence by refusing to work in the mine, insisting on serving his term in prison but not in forced labor.

To his refusal, the command responded with isolation. After completing the first isolation, he again refused to work and was placed back in the damp cell. Isolation was carried out in dark, narrow cells, and prisoners were given only one blanket at night, which was taken away in the morning.

At 5 a.m. on May 21, 1973, the guard entered Pal Zefi’s room to take the blanket. Zefi, who had been in darkness for some time, ran out of the isolation room, grabbed a metal rod, and climbed onto the terrace. The guard called on him to return to the punishment cell, but Zefi refused and warned him to stay away, saying he would strike anyone who approached.

Meanwhile, as several policemen came to help guard Fejzi Liço, the prisoners who were awake went to assist Pal. A clash began between the political prisoners and the guards of Unit 303. For many of the prisoners, everything was spontaneous and unorganized.

“Only the first shift, one third of the prisoners who were to go to the mine, was awake. I was on the second shift and was asleep at that hour. The noise woke me up. Near me were Fiqiri Mujo and Ali Hoxha. I asked them what was happening. They told me to stay quiet because I had only three months left to finish my sentence. But I could not stay still. The commotion was audible; the screams had begun.recalls former prisoner Shkëlqim Abazi. He looked out the window and saw prisoner Muharrem Dyli slapping the policeman who was hitting Pal Zefi.

“The police rushed to seize Pal Zefi, but we prisoners instinctively blocked them and even threw a few punches. The guard officer, Fejzi Liço, had his cap fall to the ground and the star on the cap was stepped on.” says former prisoner Gëzim Çela. According to another prisoner, Nuri Stepa, Pavllo Popa and Syrja Lame had stepped between the police and Pal Zefi, with the latter striking the operative.

At this point the testimonies are unclear. Fifty years later, it is difficult to reconstruct the event; however, Abazi remembers Tarti—the dog raised by his friend Fiqiri Mujo—coming out of the sleeping area and rushing to help the prisoners by attacking the police. “A man from Shkodër who was there told his companions, “Tarti has shamed us; he is fighting the police and you are just watching.” These were the sparks that ignited the fire. Everyone stood up—20, 30, 40 people, I don’t know how many. The police found themselves in a bad situation, their hats fell to the ground and they ran away.says Abazi. (His version is almost confirmed by the file on the event, according to which the police left because the situation had become tense).

Tarti, the prisoners’ dog, was executed as an insurgent after the revolt. Former prisoner Nuri Stepa gives the example of the little animal to illustrate the cruelty: “They shamelessly even shot the dog because it sided with us against the police. It lunged at the police and they fell into the pit.

HOURS OF THE UPRISING

After the initial tension and the withdrawal of the police, calm seemed to fall over the camp. Part of the first shift had gone to work in the mine.

The documents of the file suggest that there were no developments in the camp until 15:30, when the operational-investigative group arrived and Pal Zefi was arrested, followed by Syrja Lame, who was taken to the isolation room. But when the group tried to arrest Pavllo Pope and were escorting him to the isolation room, Pavllo escaped from the police and ran into the crowd of prisoners, who immediately took him under protection, shouting ““either death or freedom,” “we will not work in the galleries,” “you are murderers" etc.

The camp was now under the control of the prisoners, who broke the emulation boards with communist slogans, while on the evening of May 21 the isolation cells were opened and those held there were released. Some of the prisoners went out onto the terrace and into the roll call square. Witnesses say that Skënder Daja, Dervish Bejko, and Bashkim Fishta began to give speeches and recite anti-communist poetry. In an interview with “Newsbomb,” Nuri Stepa describes the hours of the revolt with emotion: “We shouted “down “Communism” and “down with Enver Hoxha.” Skënder Daja, whom we called “the little boy,” called on the army to join us, saying they were our brothers. The roll call square was full, while helicopters flew overhead. Across from the command building tanks had also arrived. At 1 a.m. on May 22, the flag without the communist star waved in the camp. The red cloth was taken by Rexhep Lazri from a blanket, while the eagle was painted by Mersin Vlashi. The flag was raised by Gjet Kadeli, Rexhep Lazri, and Murat Marta, while Ndrec Çoku stood guard. At one point an automatic burst began. Bullets passed over our heads. They were shooting at the flag, but not a single bullet hit it.”.

Two hours after the revolt’s flag began to wave, Deputy Minister Feçor Shehu had arrived at the camp. The file notes the time as 03:00 in the morning. Officially, at 08:00 the command made an appeal to the prisoners. Nuri Stepa, the witness speaking to “Newsbomb,” is one of the three prisoners who went to speak with Shehu.

““He had arrived at night. In the camp it was said that Kadri Hazbiu was with him. Koço Papa had gathered us in the canteen, representatives from every region, to set our demands, where we stated that we sought not to be re-sentenced, not to work in the mine, etc. We wanted Feçor Shehu to come down to talk to us, but he said a delegation should come up. Then I went out with Paulin Vata, who had been an officer.”

“We passed the lower camp area and were in the danger zone. Both sides were outside the buildings, but they could have killed us. A friend of mine, Bep Konomi, grabbed my hands when I went out and said, ‘Don’t go out, they will kill you so they can suppress us here.’ But we went out. The meeting was a battle meeting. I gave the letter with demands to a policeman.”

Feçor Shehu ignored the requests and, after asking who they were, told them they had to inform the others to separate those who did not want to work, while they themselves would find the guilty ones.

Suddenly, from the crowd of prisoners, says Stepa, Hajri Pashaj broke away and approached the delegation. "Feçori asked who he was, and Hajri introduced himself. Feçori said, “You are the son of Zenel Pashai, the one who killed the old men and women of Hekal.” “No,” Hajri replied, “you forgot that you once held the reins of the horse,” recalls Stepa, while Shkëqim Abazi adds that “Pashai and Feçori were from the same area.” but“Hajri said, ‘There is no bigger criminal than you, you are a bootlicker. You licked Zenel Pashai’s boots when he got off the horse, you offered your back for his foot. You are a criminal.’ Hajri’s conversation with the deputy minister became very vulgar… I am a direct witness.”The delegation went down into the camp, after Hajri Pashaj warned that Feçor Shehu’s end would come from his own people, as would later happen.

Below they were met with cheers. By then the prisoners had gone two days without going to the mine and also two days without food, while the command had cut off their water.